IS IT A CRISIS, SHOULD IT MATTER?

IS IT A CRISIS, SHOULD IT MATTER?

By Judge David Langham

There has been ample discussion of Worker’s Compensation in recent years. I was recently at a meeting where the system and potentials for reform were discussed. The question arose, “where is the crisis?” Essentially the sentiment is that absent acute distress there is no perceived necessity of intervention. That is, the systems do not need attention, legislative or regulatory, absent some crisis.

There has been ample discussion of Worker’s Compensation in recent years. I was recently at a meeting where the system and potentials for reform were discussed. The question arose, “where is the crisis?” Essentially the sentiment is that absent acute distress there is no perceived necessity of intervention. That is, the systems do not need attention, legislative or regulatory, absent some crisis.

That perspective is not isolated or new. There are those who perceive that legislative interventions in workers' compensation have ever only occurred when a crisis was perceived. Similarly, it seems plausible that there are literally millions of people today who are individually in no acute personal distress. Their personal health is not in crisis, although they may experience issues that are potentially affecting their longevity. Because they are not in acute distress, they do not seek either care or change. Instead, they accept a progressive onset of symptomatology or signs.

A perceived flaw of the American medical system is that attention and compensation are too often focused on acute problems. If an individual seeks healthcare, in a preventative sense, the societal inclination is for that to be the sole financial responsibility of the individual. However, if that same individual allows their health to decline and exacerbate, our system seems inclined towards at least a partially socialized response once the condition reaches crisis stage. There are complaints that too many therefore eschew preventative medicine because of cost or simple ambivalence.

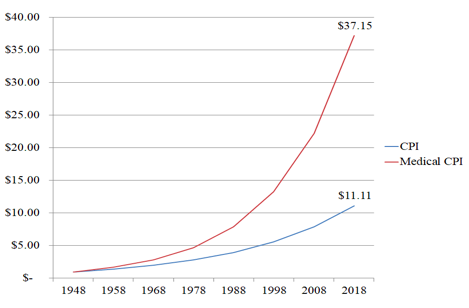

What do we know about medicine in America? Well, the cost we pay is increasing far more rapidly than the overall consumer price index, and has been for decades. See The Conundrum of Medical Inflation. According to the American Medical Association, America spends about three trillion dollars annually on medical care, about $10,000 per person. Almost one trillion dollars of that is on hospital care alone. Hospital care, the most intense provision of medical treatment, accounts for a third of total expenditure.

The Journal of the American Medical Association reports that our spending is nearly double that of other "high income countries." It consumes nearly 30% of our gross domestic product (GDP). We are spending significant money, but we are not on top in life expectancy. Worse, we have the highest infant mortality in the countries studied. Our medical system needs reform. It certainly is in crisis. There are those who advocate that we need to pay providers based on their success, not upon how many procedures they perform. They advocate shifting focus from treatment to prevention. We need to figure out a way to deliver medical care proactively, to assure health, instead of focusing so intently upon on crisis care.

A report from the Center for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that we spend about 3% of our medical expenditures on preventative care. We spend much more on treating cardiovascular disease (14%) and injuries (12%) than we spend overall on preventing problems. The CDC says that about 57% of what we spend is on inpatient hospital care. The fact is that with our health, we seem inclined to wait for, then treat, the crisis. Perhaps this is ingrained in us? Through our dietary, exercise, and preventative care choices we create our future, then we expect medicine to step in and save us when the diabetes, heart disease or other malady strikes. That is, when we are finally in personal crisis.

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) notes that studies have "linked one half of the mortality in the United States from the 10 leading causes of death to lifestyle-related behaviors"; half of the mortality rate? It notes that government advocates of change focus on a reasonably simple "five lifestyle factors" including: "tobacco use, overweight/obesity, lack of physical activity, substance abuse, and irresponsible sexual behavior." The Academy notes that there is evidence supporting the value in preventative care for these. It is effective for addressing illness before a crisis results. And, it has been demonstrated to also be cost-effective. This has led some payers to "seek out all patients" they cover "who can potentially benefit from the" preventative care.

An easy example is obesity, a health risk among our greatest challenges. Obesity if a problem for 40% of the American population, about 93 million people, according to the Center for Disease Control. Unlike so many things that can be wrong with our bodies, unnoticed, and unexpected, obesity is pretty apparent (I see myself in the mirror and know I need to shed pounds). I do not need a physician to tell me I am overweight. We are aware of the impact of body weight, and yet we struggle to address it. We spend billions of dollars annually in our assault on this apparently impregnable foe.

The decisions we make about our own health are important. We can understand that a colonoscopy or a mammogram is a good idea. We know that adjusting our diet, increasing our exercise, and regular check-ups are positive; but, too many of us are instead watching for, waiting for, that crisis. Until we have the symptoms, why go to the doctor, decrease our cholesterol, monitor our blood pressure, or get off that couch? Why are we so individually focused on awaiting symptoms, or even ignoring symptoms (increased frequency of shortness of breath) and awaiting that crisis (heart attack)?

There is evidence that patient education is productive. In Improving health outcomes with better patient understanding and education, the authors note similar mortality contributions as discussed by the AAFP. It stresses that "nearly 80% of premature deaths were attributed to just three behaviors in the list – tobacco use, dietary pattern, and physical activity level." If we would individually address only three aspects of our lifestyle, we could have a tremendous impact on our health. Although this article notes benefits from patient education, it concedes that efforts directed at some disease processes have met mixed results; diabetes is discussed in this regard.

According to the Center for Disease Control "100 million U.S. adults are now living with diabetes or prediabetes." That means "More than a third of U.S. adults have prediabetes, and the majority don’t know it." These are Americans who likely note some symptoms, perceive some risk factor(s), but do not seek medical care or lifestyle change. They await the onset of more serious symptoms before seeking medical care. Where the personal cost of dietary change or exercise might have been preventative, the societal cost of treatment following diagnosis is monetarily more significant.

On an individual level, too many people are inclined to await the crisis. Perhaps we should not be surprised if we are collectively, legislatively, in the same mindset? Are our reforms proactive to prevent societal challenges or are we reactive to issues only when the statutorily caused symptoms become unmistakable? In considering the efficacy of our workers' compensation systems, should we be focused on the question "where is the crisis," or should we instead focus on asking critical questions about system vitality, accessibility, and equity? It is plausible that attention should be focused and preventative, now?

There are aspects of workers' compensation that would benefit from attention. Certainly, we might validly say they are not in crisis. But, that approach falls into the same fallacy with which we see so many addressing their personal health. Maybe it is time, now, for workers' compensation systems to focus on the potential for problems. Focus today on systemic issues akin to our personal lifestyle choices of diet and exercise could improve both the strength and vitality of the workers' compensation safety nets across the continent. We could strengthen our resolve and our foundations, such that the crisis perhaps never comes.

Or, we can collectively ignore the signs and early symptoms. We can wait for the serious symptoms, the system disabilities or failures. We can postpone and deny. But, this will likely merely lead us as inexorably to reforms and corrections. Unfortunately, once the more serious symptoms have appeared, those costs may similarly be more expensive and painful that the lifestyle choices we might make now. The choices we are afforded once the system is in crisis may be far more limited than what we can do today working from a reasonably healthy foundation and strengthening against the onset of future symptoms.

Can we learn strengthening and lifestyle lessons for our industry from the documented challenges of our current personal health crisis?

Comments

Post a Comment